PsychInsight: A high-level API for creating and epxloring novel face stimuli#

Written by Stefan Uddenberg

Introduction#

Take a look at the image below. What do you see? The contours and colors of the image coalesce into an easily nameable percept: a human face. But your percept is likely not so generic; what can you tell me about the face? When we look at such a photograph, in some sense we can’t help but read (into) it. There are some features that we can realiably read “out” or extract from face photographs, such as age (Henss, 1991; Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998). However, we also often read “into” faces, as when we form (often misguided) impressions of others’ personalities solely on the basis of a single image (for a review, see Todorov, 2017). We form these sorts of impressions extraordinarily quickly — many perceived attributes reach reliable self-agreement at only 33-50ms stimulus exposures (e.g., Colombatto, Uddenberg, & Scholl, 2021; Todorov et al., 2009) — and early in life, with some facial impression dimensions coming “online” at only 3 years old (Charlesworth et al., 2019). Crucially, such face judgments often show high levels of agreement between perceivers, allowing scientists to create generative models (Gerig et al., 2018; Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008; Peterson, Uddenberg, Griffiths, Todorov, & Suchow, 2022) that can help elucidate not only the features of images driving such impressions, but also the boundary conditions and real-world consequences of such biases (Sutherland et al., 2017). It is important to note that these are not models of reality, but of impression formation — they reflect what (the experimentally sampled) people think an attribute looks like in particular photographs of faces. They act as mirrors that reflect the psychological processes of perceivers, allowing social scientists to transform bias itself into the object of study, or to leverage what we know of how such biases express themselves in order to explore yet subtler effects (Uddenberg & Scholl, 2018). For example, one can use synthetic faces manipulated along perceived attributes to explore how stereotypes propagate, even when there is no evidence for the stereotype at all (Uddenberg, Thompson, Vlasceanu, Griffiths, & Todorov, 2023).

An example of our synthetic face stimuli.

In order to study how we judge, perceive, or remember faces, we must use face stimuli. Broadly speaking, these stimuli can either be “real” (e.g., photographs of real-world individuals) or “synthetic” (e.g., computer-generated images, drawings, etc.). Both approaches come with tradeoffs. On the one hand, real stimuli are ecologically valid and entirely convincing to participants, but they often lack in diversity (e.g., representing different racialized groups or a wide range of emotional expressions) and ease of experimental control (e.g., requiring the manual use of photo editing software to transform the stimuli in the precise ways one might need). In addition, there are real privacy concerns with using such real-life stimuli — imagine having your photo shown to thousands of strangers to be rated on all sorts of dimensions, perhaps on a job or dating website! — which necessitates restrictions on how they are used in experiments, and sometimes, even how they are presented in papers and conferences (Ma et al., 2015). Lastly, as more and more labs utilize online experiment participant pools, widespread use of face datasets may become (or may already be) a problem, with fewer and fewer (stimulus-)naïve participants available for testing.

On the other hand, computer-generated impression models have a few key advantages, including the elimination (or, at the very least, extreme mitigation) of privacy concerns in IRB-approved research, as well as greater ease of experimental control. However, there are two salient and common disadvantages: (1) lack of realism — the most popular computer-generated images in use are very obviously computer-generated (Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008) — and (2) lack of accessibility, often being limited to the research group that created them via explicit access controls or implicit technical and knowledge barriers. Last year, we published a paper that, among other things, attempted to mitigate the problem of realism (Peterson et al., 2022). This chapter marks our first step toward solving the latter issue: here, we provide a high level API for the generation, transformation, and inference of face stimuli along dozens of perceived attributes of psychological interest. The face above is one example of the kind of stimuli that you will be able to create by the end of this chapter. This chapter will not cover the details of how these models were made, as they have already been documented in detail. Instead, you may refer to our work in PNAS (Peterson et al., 2022) and NVIDIA’s CVPR paper (Karras et al., 2020) if you are interested in understanding the experimental and computational approaches taken.

Getting started#

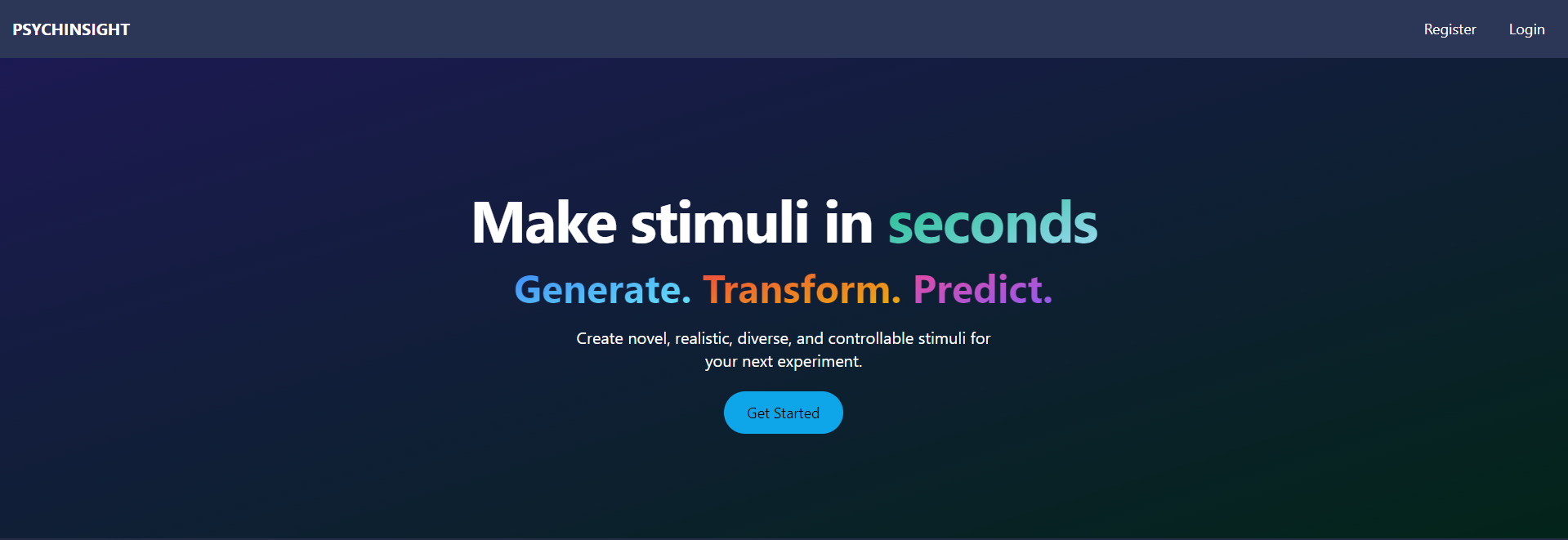

To start, all you’ll need is a web browser. We’ll be making an account and exploring some basic features of the API from a simple frontend.

First, head to the application website and click on the “Get started” button or the “Register” button within the navigation bar toward the top right of the page.

Fill out the registration form (including the project description section) and click “Submit”.

Check your email for an account verification link and click on it.

After you’ve been verified, you should be able to use your credentials to login.

Once you have an account, login using the “Login” button toward the top right of the page.

After logging in:

You will automatically be directed to the “Generator” app (described in more detail below).

At the home page, also accessible via the “API Token” page, you will be able to copy your access token by pressing the relevant button onscreen. Your access token is a long string of characters that you can use as a credential to access the API from either the frontend or your chosen means of consuming APIs in general. It expires after a set period of time.

You can view your profile details at the “Profile” page. The ability to edit (at least some of) those details will come in the near future.

Once your email is verified and your account is approved, you should be able to see and click on the “Generator” button, once again, toward the top right.

The landing page of the frontend.

Using the Generator#

The “Generator” app is a simple face stimulus generator and explorer that showcases some of the features of the API. The more advanced features can be used by directly interfacing with the API without the mediation of the frontend (more on that below).

Click the “Generate” button to create a new face.

After the image appears, the sidebar will guide you through the next steps. First, a search box of perceived attributes will appear. Upon selecting a perceived attribute, you can use the slider or the input box above to select your desired (predicted) level of that perceived attribute for the new face. You can also choose up to 2 attributes to hold constant in the process using the input box below. Click “Transform” when you would like to see the result, and the image should be updated in short order.

In the frontend application, values are limited to between -4 and +4 standard deviations from the mean predicted judgment (centered at 0). The images are more susceptible to artifacts and potential misuse past these values.

The math works such that you can control for any number of attributes. However, in practice, the images don’t look controlled. This becomes more obvious the more perceived attributes you attempt to hold constant.

You can toggle the judgment predictions with the “Show predictions” toggle. They are shown below the image in table format, and the modification sliders are automatically set to those values.

The Generator application at work.

Using the API directly#

The API is agnostic to what program (e.g., Insomnia, Postman, curl) or programming language (e.g., Python, R, JavaScript) you use to make requests. It simply requires that requests be made to certain endpoints in certain formats. The documentation can be seen at {redacted_api_url}/docs along with a simple interface for testing out these different endpoints. Many of them require a valid token (which you can copy from the main application) from an approved account — you can click the green “Authorize” button at the top right of the screen in order to use those endpoints, or include the token in your authorization header if making requests on your own.

Direct use of the API allows for the generation, transformation, and prediction of many, many faces at once, whereas the “Generator” frontend application only allows you to explore one face at a time — we’re still working out what the appropriate UX should be when using a web browser for such requests, and your feedback and suggestions will surely come in handy!

Technology stack#

The API is made with FastAPI on top of PostgreSQL, deployed on Railway. The frontend is made with Sveltekit and the Skeleton UI framework, deployed on Vercel. All face operations are performed by an AWS EC2 instance running custom code on top of StyleGAN2.

References#

Charlesworth, T. E. S., Hudson, S. T. J., Cogsdill, E. J., Spelke, E. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2019). Children use targets’ facial appearance to guide and predict social behavior. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1400–1413.

Colombatto, C., Uddenberg, S., & Scholl, B. J. (2021). The efficiency of demography in face perception. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 83(8), 3104–3117.

Gerig, T., Morel-Forster, A., Blumer, C., Egger, B., Luthi, M., Schönborn, S., & Vetter, T. (2018, May). Morphable face models-an open framework. In 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018) (pp. 75-82). IEEE.

Henss, R. (1991). Perceiving age and attractiveness in facial photographs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21(11), 933–946.

Karras, T., Laine, S., Aittala, M., Hellsten, J., Lehtinen, J., & Aila, T. (2020). Analyzing and improving the image quality of StyleGAN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (pp. 8107–8116).

Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1122–1135.

Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1998). Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social judgments. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 93–161). Academic Press.

Oosterhof, N. N., & Todorov, A. (2008). The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(32), 11087–11092.

Peterson, J. C., Uddenberg, S., Griffiths, T. L., Todorov, A., & Suchow, J. W. (2022). Deep models of superficial face judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(17), e2115228119.

Sutherland, C. A. M., Rhodes, G., & Young, A. W. (2017). Facial image manipulation: A tool for investigating social perception. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(5), 538–551.

Todorov, A. (2017). Face value: The irresistible influence of first impressions. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400885725

Todorov, A., Pakrashi, M., & Oosterhof, N. N. (2009). Evaluating faces on trustworthiness after minimal time exposure. Social Cognition, 27(6), 813–833. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2009.27.6.813

Uddenberg, S., & Scholl, B. J. (2018). Teleface: Serial reproduction of faces reveals a whiteward bias in race memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(10), 1466–1487.

Uddenberg, S., Thompson, B., Vlasceanu, M., Griffiths, T. L., & Todorov, A. (2023). Iterated learning reveals stereotypes of facial trustworthiness that propagate in the absence of evidence. Cognition, 237, 105452.

Contributions#

This notebook was authored by Stefan Uddenberg. Code for the API and/or models was contributed by Stefan Uddenberg, Rachit Shah, and Daniel Albohn. Special thanks to Joshua Peterson and Jordan Suchow for their pioneering work on the first version of the underlying face modeling code, circa 2021, and to NVIDIA for releasing the open source models and datasets used to underpin our current work.